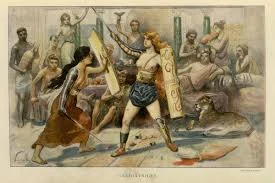

Female participation in the gladiatorial games of Ancient Rome has long fascinated historians, especially because it challenges the widespread assumption that the arena was an exclusively masculine domain. Although the overwhelming majority of gladiators were men, the Roman world did indeed witness the emergence of female fighters known as gladiatrices—a rare and striking phenomenon that captured both public curiosity and elite disapproval. These women were few in number and often regarded as exotic spectacles, yet their existence provides a nuanced window into Roman society, gender roles, and the cultural obsession with power, violence, and entertainment. The fact that Roman audiences could accept women in such a brutal and highly ritualized profession reveals as much about Roman social values as it does about the individuals who stepped into the arena. Understanding the world of the gladiatrix requires piecing together archaeological evidence, historical accounts, and cultural analysis, all of which help illuminate a group of women who defied societal expectations in ways that still intrigue us today.

While male gladiators dominated the amphitheaters of the Roman Empire, historical and archaeological records confirm that female gladiators—though extremely rare—did take part in combat. These women existed at the margins of Roman spectacle culture, and their presence often carried a shock value that enhanced the entertainment factor for spectators. Written accounts from Roman authors, including Cassius Dio and others, describe women fighting in the arena or participating in mock hunts, sometimes as part of elaborate festival programs designed to impress the public or honor visiting dignitaries. The fact that female participation was notable enough to be documented by elite writers underscores how unusual it truly was. Because Roman society expected women to remain in domestic or socially modest roles, any woman who entered the gladiatorial arena boldly violated these norms, prompting reactions ranging from fascination to ridicule.

What makes the existence of gladiatrices particularly compelling is how their rarity shapes the historical narrative. Unlike male gladiators, who were often prisoners of war, slaves, or condemned criminals, many of the women who fought appear to have been free individuals, possibly motivated by personal ambition, financial pressure, or a desire for public attention. Their presence in the arena also reflects the evolving nature of Roman public entertainment, which constantly sought novelty to satisfy increasingly jaded audiences. As spectacles grew more elaborate, the addition of female fighters provided an exotic and sensational variation in a culture that thrived on visual and emotional extremes. Yet female gladiators were not universally celebrated. Many Roman elites criticized their inclusion in the games, arguing that their participation represented moral decline or a perversion of traditional gender hierarchies. Over time, this criticism contributed to legal restrictions and eventual bans on women appearing in the arena, revealing the tension between public entertainment and social conservatism in ancient Rome. Even so, the historical traces they left behind demonstrate that gladiatrices were not mere legend but living participants in one of the most iconic institutions of Roman culture.

To fully appreciate what it meant to be a female gladiator, it is necessary to consider the broader social context of the Roman world. Gender roles in ancient Rome were deeply ingrained, with women generally excluded from political life and often confined to roles centered on family, modesty, and domestic responsibilities. A woman who chose—or was compelled—to fight in the arena therefore occupied a space of extreme social transgression. Some historical accounts suggest that certain gladiatrices were enslaved or punished, but others likely volunteered, especially during the imperial period when public games took on a more theatrical and celebratory tone. Voluntary participation by women was often viewed as scandalous, especially among the upper classes who saw female modesty as a pillar of social order.

Despite their controversial status, female gladiators underwent training similar to that of their male counterparts. They trained in specialized schools, learned weaponry, and participated in ritualized combat. However, it is likely that their fights were staged less frequently and with more emphasis on spectacle rather than endurance, given the rarity and novelty of their presence. Evidence suggests that their costumes and equipment may have been adapted to accentuate the extraordinary nature of their participation, perhaps emphasizing athleticism or exoticism to heighten audience excitement. Roman entertainment culture was deeply performative, and gladiatrices became part of that performance—challenging gender norms while simultaneously being shaped by them.

Social attitudes toward these women were mixed. On one hand, a gladiatrix was a curiosity, a person whose defiance of feminine norms made her both a spectacle and a symbol of society’s shifting boundaries. On the other hand, critics saw them as symptoms of cultural decline, arguing that women abandoning their traditional roles signaled weakening moral foundations. These critics often overlooked the fact that the arena itself was a space of inversion and exception, where normal rules did not always apply. There, bravery, skill, and spectacle mattered more than social expectations. Thus, the gladiatrix existed in a unique liminal position: simultaneously condemned and celebrated, marginalized yet thrust into the public eye, controlled by societal forces yet capable of claiming a form of agency through the very act of fighting.

While written accounts provide a foundation for understanding gladiatrices, archaeological discoveries have added depth and nuance to the picture. One of the most significant pieces of evidence is a relief found in Halicarnassus (modern-day Turkey) depicting two female gladiators named Amazon and Achillia. This relief portrays them in active combat, labeled in a style similar to that used for male gladiators, confirming that female fighters did indeed participate in structured events. The inscription suggests that the match ended in a draw, a typical outcome when both fighters displayed impressive skill. Such depictions reinforce the idea that women were trained and recognized in formal gladiatorial categories, not merely added as comedic or symbolic performers.

Archaeologists have also found remains believed by some scholars to belong to female fighters, though these interpretations remain debated due to limited physical evidence. In particular, a burial site in Southwark, London, uncovered the remains of a woman buried with artifacts reminiscent of those associated with gladiators—oil lamps depicting arena scenes, objects related to combat, and signs of an elevated social status. While absolute identification remains speculative, this context raises the possibility that female fighters enjoyed recognition beyond the arena, perhaps even acquiring fame or patronage in life. These findings challenge the assumption that gladiatrices were marginal figures; instead, they may have held a form of subcultural prestige similar to that enjoyed by some male gladiators.

The scarcity of archaeological evidence does not undermine their existence; rather, it reflects their rarity. Because female participation was uncommon and eventually subject to legal restriction, fewer physical traces would naturally remain. Written records indicate that Emperor Domitian featured women in the games during his reign, including in nighttime spectacles designed to thrill audiences. Yet by the time of Emperor Septimius Severus, the presence of female gladiators had become such a source of controversy that he issued an official ban in the early third century CE. This prohibition reveals how prominent their participation had become, at least in certain circles, and indicates that despite the rarity of gladiatrices, they were visible enough to spark imperial intervention. Each archaeological discovery and historical reference reinforces a broader understanding of female fighters as rare but significant contributors to the dramatic world of Roman spectacle.

Although female gladiators were few in number, their cultural impact resonates even today. Their existence forces modern audiences to reconsider the complexity of Roman society and the ways in which gender, power, and entertainment intersected. The gladiatrix embodied a direct challenge to the expectations placed on women, stepping into a profession centered on strength, violence, and public display. Their participation hints at the fluidity and contradictions of Roman cultural norms. On one hand, society imposed strict boundaries on female behavior. On the other, the appetite for spectacle and novelty was so strong that women could be thrust into—and even celebrated within—a hypermasculine arena.

The legacy of gladiatrices extends beyond ancient history into modern interpretations of female empowerment. Their stories, though fragmented, contribute to a broader understanding of women in antiquity as active participants in public life, not merely passive figures confined to domestic spaces. They remind us that history is full of individuals who defied convention, even in societies with rigid hierarchical structures. Modern popular culture, academic research, and museum exhibitions have embraced the figure of the female gladiator, exploring her symbolic importance as a representation of resilience, strength, and agency. Yet it is equally important to acknowledge the complexity of their roles. The arena was a brutal space, and participation often came at the cost of freedom, autonomy, or even life. For some, becoming a gladiatrix may have been a desperate decision or one forced upon them. For others, it represented an opportunity for attention, power, or personal reinvention in a society with limited avenues for female independence.

The historical memory of these women continues to evolve as new discoveries emerge and as scholars reinterpret existing evidence. Their existence is a testament to the diversity of experiences in the ancient world and a reminder that history is never as straightforward as modern assumptions might suggest. By examining the lives and roles of gladiatrices, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complexities of Roman entertainment culture and the ways in which individuals navigated its dangers and opportunities. Their legacy endures not only in the annals of history but in the imagination of anyone captivated by stories of those who stepped beyond the bounds of their era to carve out their place—however briefly—on the sands of the arena.

Contact us: info@tophistoryfacts.com

© 2026 tophistoryfacts.com - All rights reserved. Solution: Vileikis.lt